- Legendary Winning Trades: Market Moves That Made History

- George Soros and Black Wednesday: Breaking the Bank of England

- Jesse Livermore: The Man Who Shorted the Roaring Twenties

- Paul Tudor Jones: The Trader Who Saw It Coming

- John Paulson’s Big Short: The $15 Billion Bet That Broke the System

- The Bet That Built Buffett: American Express and the Salad Oil Scandal

- Andy Krieger vs. the Kiwi: The Trade That Shook a Currency

- Legendary Losing Trades: Financial Bets Gone Spectacularly Wrong

- Long-Term Capital Management: When Genius Blew Up the System

- Barings Bank: The Rogue Trader Who Sank a 233-Year-Old Institution

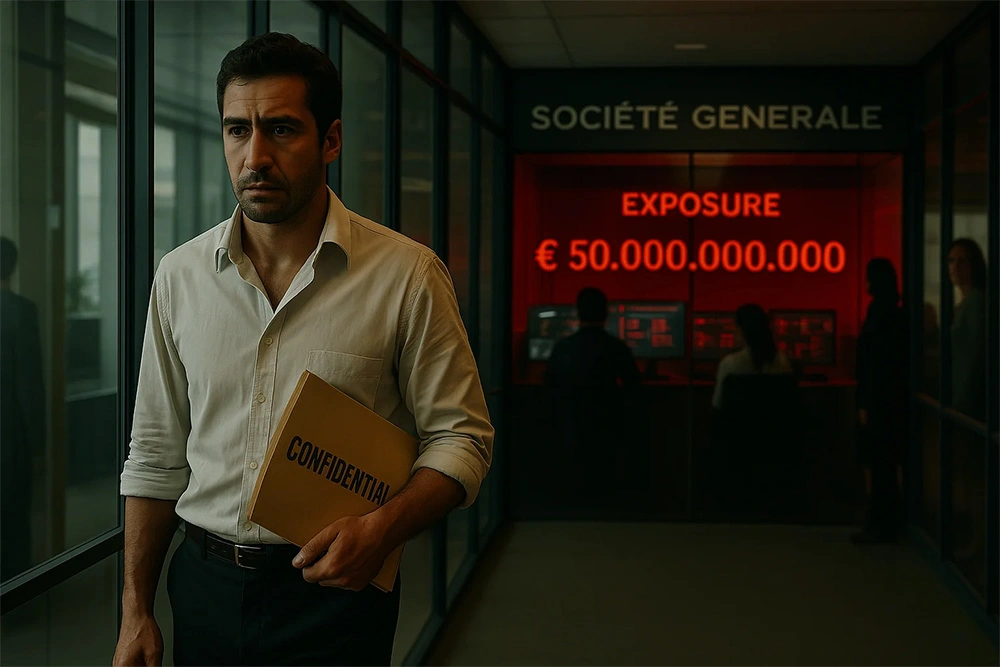

- Société Générale: How a €50 Billion Bet Slipped Through the Cracks

- Amaranth Advisors: The $6.6 Billion Gas Gamble That Went Up in Smoke

- The Hunt Brothers: How Two Oil Heirs Tried to Corner Silver and Lost Everything

- Lessons from Legends: Why Trading Is a Survival Game

Market history isn’t short on spectacle. Think audacious bets that reshaped global finance, or slow-motion disasters that entire risk departments somehow failed to see coming. This isn’t just a catalogue of triumphs and implosions. It’s a study in conviction, hubris, timing, and, at times, outright delusion.

They all have one thing in common: risk. Either misjudged or masterfully handled.

Whether the instrument was currency, commodities, tech stocks or some Frankenstein credit product nobody really understood, these weren’t just lines on a trading terminal. They were turning points. Some changed the game. Others served as blunt reminders of why the rules exist in the first place.

When confidence gets ahead of caution, this is what happens. And sometimes, it works.

The names are legendary. The figures border on absurd. But their real value lies in the lessons they leave behind. These trades reveal what happens when human psychology collides with a market that cares little for who gets it right. What matters is who survives.

Legendary Winning Trades: Market Moves That Made History

Every genius trade looks obvious in hindsight. At the time, most looked reckless.

But the ones that made history weren’t lucky punts or wild speculation. They were grounded in conviction. The kind that sees you pile in while everyone else is scrambling for the exits.

These weren’t shots in the dark. They were deliberate, high-stakes decisions built on deep research, sharp instincts, and the nerve to move early. That often meant standing alone, while the rest of the market was convinced you’d lost the plot.

What follows isn’t just a list of profitable trades. These moves bent markets, rewrote playbooks, and turned bold calls into financial folklore.

George Soros and Black Wednesday: Breaking the Bank of England

Some traders make money. Others leave a mark. On 16 September 1992, George Soros managed both.

While most of the City braced for a showdown in the currency markets, Soros and his Quantum Fund delivered one of the most audacious trades in history. By the time the dust settled, the UK had been forced into a humiliating U-turn, and Soros was up more than $1 billion. All in a day’s work.

At the heart of it was Britain’s stubborn commitment to the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. The government was hell-bent on keeping the pound pegged at 2.7 Deutsche Marks, despite the economy limping along with little justification for that valuation. Interest rates were ratcheted up to 15 percent to protect the peg. Reserves were drained. Confidence, however, was nowhere to be found.

Soros saw the bluff for what it was. While the Treasury clung to its illusions, he quietly amassed a colossal short position, borrowing and selling pounds in bulk. Then came the coup de grâce: he made his position known. Loudly. That signal tipped an already jittery market into full-blown panic.

The selling turned relentless. The government blinked. The pound was pulled from the ERM and allowed to slide freely, shedding around 15 percent in the days that followed.

Soros didn’t just make money. He earned a nickname that stuck: the man who broke the Bank of England. Ironic, really. Because while the government licked its wounds, the economy eventually found its feet. A weaker pound gave exports a boost, inflation fell, and growth returned.

The takeaway? Markets may be irrational at times but try standing in the way when they’re right. You’ll get flattened.

Lessons for Traders:

- Conviction wins. Soros didn’t just suspect the peg would break, he went all in, armed with fundamentals.

- Markets crush bad policy. Governments can fight reality for a while, but when the numbers don’t add up, they lose.

- Cut losses or get cut down. The Bank of England held its ground too long, turning a bad situation into a disaster.

Jesse Livermore: The Man Who Shorted the Roaring Twenties

Jesse Livermore wasn’t just another Wall Street speculator. He was the man who saw the party getting out of hand and bet on the floor collapsing.

As the Roaring Twenties hit full swing, stocks were flying. Prices had risen fivefold, fuelled less by fundamentals and more by cheap credit. Margin debt was everywhere. Traders weren’t investing their own money; they were gambling with the bank’s. Livermore, who had made and lost several fortunes by then, recognised the signs. The market wasn’t climbing on earnings or outlooks. It was climbing because everyone assumed it would keep climbing.

By late 1929, the music started to fade. Livermore quietly built short positions as momentum slowed. Then October came, and the house of cards gave way. Black Monday and Black Tuesday wiped out 25 percent of the Dow in two days. Panic set in. Selling turned disorderly. Livermore didn’t blink. He leaned in and let the collapse do the rest.

By the end of it, he was reportedly sitting on $100 million. Adjusted for inflation, that’s enough to rival a modern tech IPO. The timing was so immaculate that the press dubbed him “the man who sold America short.”

But Livermore’s greatest trade also came with a footnote. The money didn’t last. Neither did the fame. He lost his fortune in the years that followed, a cautionary twist in an otherwise legendary career. Making the trade is one thing. Hanging onto the money is another game entirely.

Lessons for Traders:

- Recognise the bubble. Livermore saw that the market wasn’t rising on real value, it was running on borrowed money and blind optimism.

- Patience wins. He didn’t short too early. He waited for real signs of weakness before making his move.

- Profits aren’t real until they’re banked. Livermore made and lost multiple fortunes, proving that locking in gains is just as important as making the right call.

Paul Tudor Jones: The Trader Who Saw It Coming

Most traders dread a crash. Paul Tudor Jones looked one in the eye, placed his bets, and walked away with a fortune.

In October 1987, Wall Street was riding high. Euphoria was everywhere. But Jones, studying the charts with a historian’s obsession, spotted something unsettling. The technical pattern forming in 1987 looked uncannily like 1929. The U.S. deficit was swelling. Valuations were stretched thin. To him, this wasn’t a healthy bull run. It was a setup waiting to break.

So, while others bought the top with champagne in hand, Jones quietly went short through the futures market. Then came 19 October. Black Monday. The Dow collapsed by 22.6 percent in a single session, the worst one-day fall in U.S. market history. Chaos reigned. Investors froze. Portfolios evaporated.

Jones didn’t blink. His fund reportedly tripled in value, locking in around $100 million. Clients saw returns north of 200 percent.

And this wasn’t a lucky shot. Jones understood how crashes unfold. He’d modelled it, anticipated it, prepared for it. He didn’t go in swinging blindly either. The trade was wrapped in disciplined risk management, with stop-losses and capital controls baked in. While most were caught flat-footed, he stayed in the trade with conviction.

That one move didn’t just mint money. It secured his place in trading legend and proved that betting against the herd only works if your risk game is tighter than your timing.

Lessons for Traders:

- History doesn’t repeat, but it leaves clues. Jones saw 1987 as a 1929 déjà vu, proof that past crashes offer insights to those who pay attention.

- Conviction means nothing without risk management. He didn’t just go all-in. He used stop-losses to stay in the game, even if he was wrong.

- Markets crash faster than traders expect. Spot the signs early, and you’ll be on the right side of history.

John Paulson’s Big Short: The $15 Billion Bet That Broke the System

John Paulson wasn’t chasing a headline. He was quietly building one of the most profitable trades in history, not with high-frequency algorithms or frantic day trading, but with a long, deliberate view of a system cracking beneath the surface.

Plenty of traders have made billions. Very few did it by betting against the entire financial architecture of the United States.

By 2005, Paulson, a relatively unknown hedge fund manager, started picking apart the subprime mortgage market. What he found was absurd. Home loans were being handed out to anyone with a pulse, then packaged into securities, rubber-stamped with AAA ratings, and sold as if they were as safe as Treasury bonds. They weren’t. They were time bombs disguised as assets.

While Wall Street toasted rising house prices, Paulson started buying credit default swaps. These contracts acted like insurance policies, paying out if mortgage-backed securities collapsed. It was 2006, and to most, the idea of a nationwide housing crash still seemed laughable.

He didn’t flinch. The market cracked in 2007. By 2008, it broke wide open. Subprime defaults soared, banks buckled, and Paulson’s bearish trades surged. His fund banked $15 billion in profit that year. He personally earned around $4 billion, which remains one of the biggest single-year payouts in hedge fund history.

Sure, Michael Burry got there first. He spotted the rot early and helped engineer the CDS market from scratch. But Paulson scaled the short into something bigger. His version wasn’t just early. It rewrote the record books.

The headlines focused on the money. But the trade also delivered a harder truth. Markets aren’t just inefficient. Sometimes, they’re blind. Paulson showed that when the right idea meets the right structure, even the most systemic delusions can be priced, challenged, and unwound.

Lessons for Traders:

- When the herd is too confident, question it. In 2006, almost no one believed housing could crash. Paulson’s success came from seeing what others refused to accept.

- Patience is a trader’s best weapon. Paulson endured months of ridicule, but when his thesis played out, it became one of the most profitable trades in history.

- Use the right instruments for the trade. Credit default swaps gave Paulson an asymmetric bet: limited downside, massive upside.

The Bet That Built Buffett: American Express and the Salad Oil Scandal

Most legendary trades hinge on timing, speed, or sheer audacity. Warren Buffett’s 1964 play on American Express was none of those. It was slow, measured, and built on an instinct for value that ignored noise and zeroed in on what mattered.

The trigger? A fraud straight out of a financial crime farce. In 1963, a commodities trader conned a network of lenders into believing he held vast reserves of soybean oil. The trick? A thin layer of oil floating on top of seawater in storage tanks. American Express had backed the loans and found itself $58 million lighter when the whole thing unravelled.

The market’s reaction was swift. American Express shares were nearly halved, falling from $65 to $37. Confidence collapsed. Most investors ran.

Buffett didn’t. He saw the scandal for what it was: a reputational hit, not a fatal blow. The fundamentals of the business were intact. Travellers’ cheques and charge cards still ruled the payment space. But he didn’t just trust the numbers. He went out and checked himself, walking into shops and restaurants to see if people were still using their Amex cards. They were.

That was enough.

He moved decisively, buying a 5 percent stake in the company for $20 million. It was a bold move. The position made up more than 40 percent of his partnership’s capital at the time. But he was right. American Express recovered and surged through the decade. By 1973, his investment had ballooned past $200 million.

It wasn’t just a big win. It was a lesson in temperament. While others saw a crisis, Buffett saw a durable brand, steady consumer behaviour, and a rare valuation window. This wasn’t speculation. It was conviction, paired with real-world evidence.

Lessons for Traders:

- Fear creates opportunity for those who stay rational. Buffett ignored panic and focused on real business fundamentals.

- Information isn’t just in balance sheets. Instead of relying on analyst reports, he watched real-world consumer behaviour.

- High conviction requires high stakes. He committed 40% of his capital, but only because his research gave him an edge.

- Great trades aren’t always fast trades. Sometimes, holding through recovery is what delivers outsized returns.

Andy Krieger vs. the Kiwi: The Trade That Shook a Currency

Most traders dream of moving the market. Andy Krieger moved an entire currency.

In the aftermath of the 1987 stock market crash, while others were still shell-shocked by equities, Krieger had his eyes elsewhere. Working the currency desk at Bankers Trust, he spotted something odd. As capital flooded out of the US dollar, certain currencies were becoming wildly overbought. One stood out more than most: the New Zealand dollar.

The Kiwi wasn’t built for the spotlight. As a relatively thin and illiquid currency, it simply couldn’t handle the scale of money chasing safety. Krieger saw the imbalance and didn’t hesitate. Using an aggressive mix of short-selling and currency options, he constructed a position reportedly larger than New Zealand’s entire money supply.

The logic was straightforward. The Kiwi was artificially inflated, and pressure would expose the cracks. That pressure came fast. In late 1987, Krieger’s positioning helped drive the Kiwi down by 5 percent in a single day. Bankers Trust banked millions almost instantly. The move sent shockwaves through the forex market. New Zealand officials reportedly called the bank in a panic, pleading for the attack to stop.

Krieger wasn’t just trading. He was playing monetary policy like a piano. The scale, the speed, and the precision were enough to catch the attention of George Soros, who brought him on board not long after.

This wasn’t just a big win. It was the kind of move that turns a name into a reputation.

Lessons for Traders:

- Small markets can create oversized opportunities. Krieger shorted the Kiwi because it was easier to move than a major currency.

- Leverage is a weapon, but it cuts both ways. A massive position can yield huge rewards but also attract regulators.

- Know when to take profits and walk away. The 5% drop was swift and brutal, but authorities can step in at any moment.

- Liquidity can work for you or against you. Thin markets amplify gains, but they can turn on you just as fast.

Legendary Losing Trades: Financial Bets Gone Spectacularly Wrong

For every well-timed fortune, there’s a disaster waiting on the other side of the trade.

These weren’t minor errors or harmless misreads. They were full-blown detonations, fuelled by leverage, blind spots, and the kind of unchecked confidence that turns a bad idea into a financial obituary.

The warnings were there. The rules weren’t just ignored; they were mangled beyond recognition. And the consequences? Brutal. Some trades didn’t just ruin portfolios. They blew up firms, roiled markets, and rewrote regulations.

So how does it keep happening? Why do people who are brilliant, credentialed, and well-capitalised still fall for the same traps? It’s not about mocking the wreckage. It’s about understanding the anatomy of a blow-up. Because buried in these disasters are lessons far more valuable than the wins.

Long-Term Capital Management: When Genius Blew Up the System

Long-Term Capital Management wasn’t your average hedge fund. It was built like a financial think tank, packed with Wall Street royalty and Nobel laureates. On paper, it was an unstoppable force. In practice, it became a masterclass in how brilliance can self-destruct.

LTCM’s core strategy was deceptively simple: bet on bond spreads converging. In normal markets, it worked like clockwork. They’d go long on undervalued government debt in places like Russia and short overpriced equivalents in the US or Europe. The trades weren’t reckless. They were treated as statistical certainties, at least in theory.

But theory doesn’t account for Russia defaulting on its debt. That happened in 1998, and it upended everything. Instead of narrowing, spreads blew out. LTCM, leveraged to the teeth at 100 to 1, found itself on the wrong side of a global panic. What should have been a temporary dislocation turned into a systemic threat.

Losses mounted quickly. In a matter of weeks, the fund lost $4.8 billion and teetered on the edge of collapse. Worse still, its trades were so large and so interconnected that its failure threatened to drag major banks and counterparties down with it. The Federal Reserve had to step in, corralling Wall Street’s biggest players into a coordinated rescue. Here’s the kicker: the trades weren’t irrational. They made sense on paper. But the paper didn’t survive contact with real-world chaos. LTCM’s downfall wasn’t just a market event. It was a reminder that even the smartest models fail when the market stops playing by the rules.

Lessons for Traders:

- Leverage cuts both ways. LTCM’s 100:1 leverage turned small miscalculations into catastrophic losses.

- Models work until markets break them. Their strategy relied on historical probabilities, but extreme events don’t care about backtests.

- No trader is bigger than the market. Even a hedge fund backed by Nobel laureates can’t fight global panic.

Barings Bank: The Rogue Trader Who Sank a 233-Year-Old Institution

Barings wasn’t just another bank. It was Britain’s oldest merchant bank, founded in 1762, with a client list that included royalty and a reputation forged through centuries of war, upheaval, and financial crisis. But all of that was undone by one man, a single terminal, and a string of increasingly desperate trades.

Nick Leeson was 28 when Barings sent him to Singapore to run what was supposed to be a safe, mechanical arbitrage operation. His job? Exploit minor pricing differences between Nikkei futures listed on separate exchanges. The strategy wasn’t glamorous, but it was meant to be low-risk and dependable.

That’s not what happened.

Rather than sticking to the brief, Leeson began making large directional bets on Japanese equities and bonds. When losses started piling up, he buried them in a secret account known internally as “88888” and told London everything was under control. It wasn’t.

Then came the Kobe earthquake in January 1995. Markets tanked. Leeson, already deep in the red, doubled down in a frantic attempt to claw back losses. The market fell further. He did it again. And again. By the time the dust settled, he’d racked up losses of $1.3 billion, which was more than twice the bank’s entire available capital.

Barings collapsed almost overnight. It was sold to ING for £1. Centuries of history, erased in a blink.

The real scandal wasn’t just the trading. It was the system that allowed it to happen. Leeson wasn’t just placing bets. He was also responsible for settling them. There was no effective compliance oversight, no meaningful separation of duties, and no one watching the watcher.

Of course, the film came next. Rogue Trader gave it a go, but even Hollywood couldn’t match the sheer absurdity of the real thing. A junior banker, left unsupervised, gambled with billions and took down a financial institution that had survived everything except itself.

Lessons for Traders:

- Emotional trading is fatal. Leeson’s downfall wasn’t a stroke of bad luck. It was driven by ego, panic, and a refusal to cut losses. Chasing the market rarely leads to recovery. More often, it ends in collapse.

- Controls aren’t optional. No trader should ever be allowed to handle both the execution and the oversight. Risk management needs to be independent, unbendable and able to say “no” when it matters most.

- One person can sink the ship. No institution is too old, too respected or too well-known to fail. All it takes is a blind spot and the wrong person exploiting it.

Société Générale: How a €50 Billion Bet Slipped Through the Cracks

You’d think after Barings, the world would’ve learned. But nearly fifteen years later, France’s second-largest bank repeated the same mistake. This time, the hole was even deeper.

The trader at the centre was Jérôme Kerviel, a mid-level operator running what was supposed to be a low-risk strategy on European equity futures. Instead, he quietly built-up unauthorised positions totalling more than €50 billion. That’s not a typo. He faked offsetting trades to disguise the scale of his exposure, manipulated internal systems, and turned the bank’s balance sheet into a personal casino.

For a while, it worked. In 2007, Kerviel was making money, and as long as the profit showed up in the right columns, no one looked too closely. Risk controls weren’t just asleep; they barely seemed to exist. Kerviel’s real positions were hiding in plain sight, propped up by a cocktail of complacency, weak oversight, and a culture far more focused on results than on rules.

Then came 2008. The trades turned against him. Société Générale was forced into a fire sale to unwind the mess, locking in $7.2 billion in losses. The bank survived, but only after scrambling to raise emergency capital. Its reputation didn’t recover quite as easily.

Kerviel was convicted on multiple charges, including breach of trust and forgery. But his defence raised an uncomfortable truth: perhaps the institution wasn’t entirely blind to what was going on. Maybe, just maybe, it only opened its eyes once the numbers went red.

And that’s the real takeaway. Kerviel wasn’t hiding. He was out in the open, thriving within a system that failed to challenge him. Like Leeson before him, he didn’t start out intending to blow up the bank. He just kept chasing the last win, until the illusion collapsed under its own weight.

Lessons for Traders:

- Don’t kid yourself. If you’re hiding losses, you’re not trading, you’re gambling. Kerviel’s trades weren’t hedged. They were naked punts, disguised with creative paperwork. And it worked, until it didn’t.

- Risk management isn’t optional. It’s not just a compliance exercise. It’s the firewall between a bad trade and an existential crisis. SocGen’s collapse was avoidable. Someone just needed to look closer.

- Hidden trades aren’t an edge. No amount of short-term success justifies a long-term blow-up. If your strategy depends on no one noticing, it isn’t bold, it’s a ticking clock.

Amaranth Advisors: The $6.6 Billion Gas Gamble That Went Up in Smoke

In the chaotic world of commodities, few blow-ups have matched the speed and scale of Amaranth Advisors. At its peak, the hedge fund managed $9 billion in assets. By the end of September 2006, it had lost two-thirds of that in a single, concentrated bet on natural gas.

The man behind it was Brian Hunter, a skilled but notoriously aggressive energy trader. His thesis was hardly absurd. He bet on a seasonal price spread, expecting winter gas contracts to rise relative to summer. The models agreed. The trade made sense. At first, it even made money.

Then came the classic mistake: he pushed it.

Rather than taking the win, Hunter doubled down. Then doubled again. Amaranth wasn’t just exposed to natural gas. It was chained to it and sinking fast. The fund ramped up its exposure to futures and options until it held one of the largest gas positions the market had ever seen.

At that scale, nuance goes out the window. When weather forecasts began pointing to a mild winter, prices slipped in the wrong direction. Margin calls started landing. Fast.

Within weeks, Amaranth had lost $6.6 billion. The fund was liquidated, and its reputation went with it.

While Hunter scrambled to stem the bleeding, others smelled opportunity. John Arnold, then trading at Centaurus Energy, reportedly made a fortune shorting Hunter’s position. One trader’s downfall became another’s banner year.

But the real story wasn’t just about a losing bet. It was about size, conviction, and the point where strategy turns into obsession. Natural gas is notoriously volatile, the spreads are thin, and the market lacks the depth to absorb a whale in distress. By the time Amaranth looked for the exits, they were already locked inside.

Lessons for Traders:

- Concentration is lethal. Amaranth’s downfall wasn’t due to market unpredictability; it was the result of staking the firm’s future on a single, massive bet in the natural gas market. Such lack of diversification is a recipe for disaster.

- Liquidity isn’t just a buzzword. Their positions were so enormous that exiting them without causing market tremors became impossible. In illiquid markets, size can be your enemy, turning manageable losses into catastrophic ones.

- Overconfidence can sink you. Buoyed by previous successes, Amaranth’s traders increased their exposure, ignoring the warning signs. Past performance doesn’t guarantee future results, especially when hubris blinds you to emerging risks.

The Hunt Brothers: How Two Oil Heirs Tried to Corner Silver and Lost Everything

In the late 1970s, Texas oil tycoons Nelson and William Hunt set out to corner the global silver market. Not metaphorically. Literally. Their goal was to buy so much of the metal that they could control its price. And for a while, they actually pulled it off.

Fuelled by a fear of inflation and a deep distrust of paper money, the Hunts started hoarding physical silver and stacking up futures contracts like it was their birthright. At one point, they reportedly controlled more than half the world’s deliverable silver supply. The price surged from around $6 an ounce to nearly $50 by January 1980. On paper, the brothers were sitting on billions.

But the paper didn’t last.

As the price soared, alarm bells rang. COMEX, the New York-based futures exchange, stepped in and changed the rules. From January 1980, traders could only sell existing contracts. New long positions? Off the table. Liquidity dried up. Panic set in. Prices collapsed. On 27 March, now known as Silver Thursday, silver lost over half its value in just four days.

Margin calls followed. The Hunts couldn’t meet them. Their silver empire, built on leverage and bravado, collapsed almost overnight. They were forced into a humiliating liquidation and reportedly lost over $1 billion in the fallout. Bankruptcy followed. So did years of litigation.

The scandal didn’t take down the financial system, but it rattled nerves across the market. And silver? It didn’t sniff $50 again until 2011. That was more than thirty years later.

The Hunt episode remains one of the clearest lessons in market mechanics. You can have capital, conviction, and even temporary control. But when the system decides it’s had enough, the rules change. When it turns, it turns hard.

Lessons for Traders:

- You can’t corner the market forever. Even billionaires run out of runway when the rules change. The exchanges hiked margins and imposed restrictions. The market doesn’t care how much metal you own. Once you’re forced to sell, it’s over.

- Parabolic moves punish late conviction. Silver’s rise was steep, but its fall was brutal. The Hunts kept piling in instead of trimming risk. In mania-driven markets, profits are paper until banked.

- Size becomes the enemy. Their position was so dominant that they became the market. When they needed to get out, there were no buyers left. Exiting under pressure turns scale into a liability.

Lessons from Legends: Why Trading Is a Survival Game

Market history isn’t shaped by caution. It’s crafted by those bold enough to risk everything, whether brilliantly or disastrously. The trades we’ve explored aren’t just cautionary tales or textbook examples; they’re real-world masterclasses on the unpredictable collision of confidence, conviction, and capital.

Some trades minted fortunes; others left craters. Yet each reinforces the same stark truth: the market doesn’t care if you’re clever, daring, or deluded. It only cares that you’re solvent when the dust settles. After all, trading isn’t about avoiding every loss. It’s about surviving long enough to fight another day.